This article is excerpted fromEvery American an Innovator: How Innovation Became a Way of Life, by Matthew Wisnioski (The MIT Press, 2025).

Imagine a point-to-point transportation service in which two parties communicate at a distance. A passenger in need of a ride contacts the service via phone. A complex algorithm based on time, distance, and volume informs both passenger and driver of the journey’s cost before it begins. This novel business plan promises efficient service and lower costs. It has the potential to disrupt an overregulated taxi monopoly in cities across the country. Its enhanced transparency may even reduce racial discrimination by preestablishing pickups regardless of race.

aspect_ratioEvery American an Innovator: How Innovation Became a Way of Life, by Matthew Wisnioski.The MIT Press

Sounds like Uber, but it’s not. Prototyped in 1975, this automated taxi-dispatch system was the brainchild of mechanical engineer Dwight Baumann and his students at

Carnegie Mellon University. The dial-a-ride service was designed to resurrect a defunct cab company that had once served Pittsburgh’s African American neighborhoods.

The ride service was one of 11 entrepreneurial ventures supported by the university’s Center for Entrepreneurial Development. Funded by a million-dollar grant from the

National Science Foundation, the CED was envisioned as an innovation “hatchery,” intended to challenge the norms of research science and higher education, foster risk-taking, birth campus startups focused on market-based technological solutions to social problems, and remake American science to serve national needs.

Today, university incubators like the CED are commonplace. Whether they’re seeking to nurture the next Uber, or social ventures like the dial-a-ride service, they all aim to transform ideas into businesses, discoveries into applications, classroom assignments into revenue, and faculty and students into entrepreneurs. Indeed, the idea that universities are engines of innovation is so ingrained that we take it for granted that it was always the case. So it’s instructive to look back to the time when the first innovation incubators were themselves being incubated.

Are innovators born or made?

During the Cold War, the model for training scientists and engineers in the United States was one of manpower in service to a linear model of innovation: Scientists pursued “basic” discovery in universities and federal laboratories; engineer–scientists conducted “applied” research elsewhere on campus; engineers developed those ideas in giant teams for companies such as Lockheed and Boeing; and research managers oversaw the whole process. This model dictated national science policy, elevated the

scientist as a national hero in pursuit of truth beyond politics, and pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into higher education. In practice, the lines between basic and applied research were blurred, but the perceived hierarchy was integral to the NSF and the university research culture that it helped to foster.

In the late 1960s, this postwar system of academic science and engineering appeared to be breaking down. Science and technology were seen as root causes of environmental destruction, the Vietnam War, job losses, and racial and economic inequality. A similar reckoning was taking place around national science policy, with critics on the left attacking the complicity of scientists in the military-industrial complex and those on the right assailing the wastefulness of ivory-tower spending on science.

In this moment of revolt, innovation experts in Washington, D.C., and the booming technology regions of California and Massachusetts began to promote innovators as the people who would bring about change, because they were different from the established leaders of American science. Eventually, a wide range of constituents—bureaucrats, inventors, academics, business leaders, and engineers—came to identify innovators as agents of national progress, and they concluded that these innovators could indeed be taught in the nation’s universities.

The question was, how? And would the universities be willing to remake themselves to support innovation?

And so it fell to the NSF to develop successful models for producing these risk-taking sociotechnologists.

The NSF experiments with innovation

At the Utah Innovation Center, engineering students John DeJong and Douglas Kihm worked on a programmable electronics breadboard.Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

In 1972, NSF director

H. Guyford Stever established the Office of Experimental R&D Incentives to “incentivize” innovation for national needs by supporting research on “how the government [could] most effectively accelerate the transfer of new technology into productive enterprise.” Stever stressed the experimental nature of the program because many in the NSF and the scientific community resisted the idea of goal-directed research. Innovation, with its connotations of profit and social change, was even more suspect.

To lead the initiative, Stever appointed C.B. Smith, a research manager at United Aircraft Corp., who in turn brought in engineers with industrial experience, including Robert Colton, an automotive engineer. Colton led the university Innovation Center experiment that gave rise to Carnegie Mellon’s CED.

The NSF chose four universities that captured a range of approaches to innovation incubation. MIT targeted undergrads through formal coursework and an innovation “co-op” that assisted in turning ideas into products. The University of Oregon evaluated the ideas of garage inventors from across the country. The University of Utah emphasized an ecosystem of biotech and computer graphics startups coming out of its research labs. And Carnegie Mellon established a nonprofit corporation to support graduate student ventures, including the dial-a-ride service.

Grad student Fritz Faulhaber holds one of the radio-coupled taxi meters that Carnegie Mellon students installed in Pittsburgh cabs in the 1970s.Ralph Guggenheim;Jerome McCavitt/Carnegie-Mellon Alumni News

Carnegie Mellon got one of the first university incubators

Carnegie Mellon had all the components that experts believed were necessary for innovation: strong engineering, a world-class business school, novel approaches to urban planning with a focus on community needs, and a tradition of industrial design and the practical arts. CMU leaders claimed that the school was smaller, younger, more interdisciplinary, and more agile than MIT.

The main reason that CMU received an NSF Innovation Center, however, was its director,

Dwight Baumann. Baumann exemplified a new kind of educator-entrepreneur. The son of North Dakota farmers, he had graduated from North Dakota State University, then headed to MIT for a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering, where he discovered a love of teaching. He also garnered a reputation as an unusually creative engineer with an interest in solving problems that addressed human needs. In the 1950s and 1960s, first as a student and then as an MIT professor, Baumann helped develop one of the first computer-aided-design programs, as well as computer interfaces for the blind and the nation’s first dial-a-ride paratransit system.

But Baumann was frustrated with MIT’s culture of defense research and engineering science, and so he left his tenured position in 1970 to join CMU and continue his work on transportation systems. There, he chartered the NSF-funded CED as a nonprofit. He purchased the bankrupt Peoples Cab Co. for a dollar, convinced the university to let him use a former parking garage as an incubator space, and worked across colleges to establish a master’s program in engineering design.

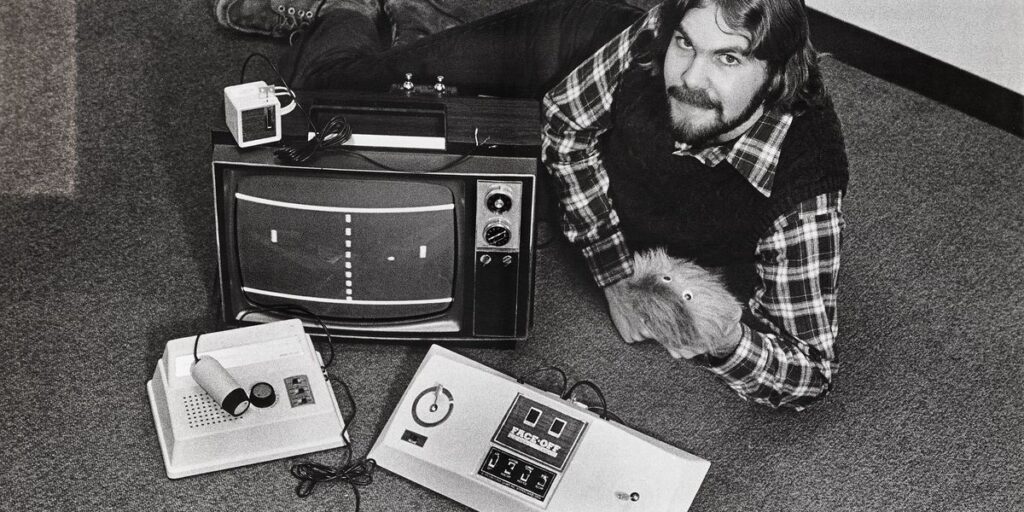

Dwight Baumann, director of Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Entrepreneurial Development, believed that a modern university should provide entrepreneurial education.

Carnegie Mellon University Archives

Baumann’s goal was to establish entrepreneurship education as a core function of a modern technological university. He wasn’t especially concerned with making money, and he cared little for nationalist rhetoric about global competition. Rather, his professed goal was to unlock human creativity in a “studio without walls, an association of people, loosely related, who communicate with each other and can get help when they need it.” Technological innovation, he argued, could never be entirely predictable because it was a project, rather than an act of scientific discovery. “A project,” he wrote, “is something that hasn’t yet happened. And the instructors and students have the common goal of seeing how it’ll turn out.”

The CED’s mission was to support entrepreneurs in the earliest stages of the innovation process when they needed space and seed funding. It created an environment for students to make a “sequence of nonfatal mistakes,” so they could fail and develop self-confidence for navigating the risks and uncertainties of entrepreneurial life. It targeted graduate students who already had advanced scientific and engineering training and a viable idea for a business.

In its first five years, the center launched 11 ventures. In addition to the reboot of the Peoples Cab Company, projects included a blood oximeter, a computer-hardware company, and a newspaper-printing technique. Many of these endeavors failed. Founders had health problems, patent disputes arose, and competitors claimed that the CED’s ventures had an unfair advantage through the weight of CMU.

Carnegie Mellon’s dial-a-ride service replicated the Peoples Cab Co., which had provided taxi service to Black communities in Pittsburgh.

Charles “Teenie” Harris/Carnegie Museum of Art/Getty Images

The CED distilled these lessons in brochures and public seminars, while faculty incorporated them into new classes. A 10-point “readiness assessment” emphasized personal reflection before any technology or market evaluation. The first rule: “Only if you have sincerely made the decision within yourself to invest time and effort, and understand that sacrifice and risk are inevitable, should you consider the life of an entrepreneur.” It aimed to show that innovation was a difficult path that could result in “personal dissatisfaction” and that one’s “family goals” must not be sacrificed in single-minded pursuit of an entrepreneurial opportunity.

A few CED students did create successful startups. The breakout hit was Compuguard, founded by electrical engineering Ph.D. students

Romesh Wadhwani and Krishnahadi Pribad, who hailed from India and Indonesia, respectively. The pair spent 18 months developing a security bracelet that used wireless signals to protect vulnerable people in dangerous work environments. But after failing to convert their prototype into a working design, they pivoted to a security- and energy-monitoring system for schools, prisons, and warehouses.

With CED assistance, Compuguard secured government contracts and millions in venture capital and grew to over 100 employees. Its first major client was the Los Angeles city school district. The two founders sold the company for what was then the largest ever return on investment by a minority-run enterprise. Wadhwani became a serial entrepreneur and is now one of Silicon Valley’s leading billionaire philanthropists. His

Wadhwani Foundation supports innovation and entrepreneurship education worldwide, particularly in emerging economies.

When NSF funding for the CED ran out in 1978, a series of long-simmering tensions erupted. At the heart of most of them was the cult of personality around Baumann, whose slapdash style conflicted with CMU’s desire to compete with new technology entrepreneurship programs at the University of Pennsylvania’s

Wharton School and elsewhere. In 1983, Baumann’s onetime partner Jack Thorne took the lead of the new Enterprise Corp., which aimed to help Pittsburgh’s entrepreneurs raise venture capital. Baumann was kicked out of his garage to make room for the initiative.

Baumann moved the CED to an abandoned YMCA building and attempted, with limited results, to help unemployed skilled laborers become innovators. The center faded, as CMU’s faculty continued to fight over the proper role of university innovation and who had the authority to teach it.

Was the NSF’s experiment in innovation a success?

As the university Innovation Center experiment wrapped up in the late 1970s, the NSF patted itself on the back in a series of reports, conferences, and articles. “The ultimate effect of the Innovation Centers,” it stated, would be “the regrowth of invention, innovation, and entrepreneurship in the American economic system.” The NSF claimed that the experiment produced dozens of new ventures with US $20 million in gross revenue, employed nearly 800 people, and yielded $4 million in tax revenue. Yet, by 1979, license returns from intellectual property had generated only $100,000.

The Innovation Centers garnered intense national and international interest. Established business schools in the United States created competing technology-innovation tracks. Visiting contingents from Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom hoped to re-create it.

Today, the legacies of the NSF experiment are visible on nearly every college campus.

Critics included Senator

William Proxmire of Wisconsin, who pointed to the banana peelers, video games, and sports equipment pursued in the centers to lambast them as “wasteful federal spending” of “questionable benefit to the American taxpayer.”

African American chemist

Grant Venerable faulted the program for its narrow conception of innovation as the purview of white men at elite universities. If supposed innovators could not address gender and racial equity “by more than a token nod,” he wrote, “they are guilty of being part of the problem.”

And so the impacts of the NSF’s Innovation Center experiment weren’t immediately obvious. Many faculty and administrators of that era were still apt to view such programs as frivolous, nonacademic, or not worth the investment.

Today, though, the legacies of the NSF experiment are visible on nearly every college campus. It institutionalized the scientific innovator-entrepreneur as a risk-taker who understood the probabilities of capital just as well as thermodynamics. And it established that the purpose of innovation education wasn’t just about breeding winners. All students, even those who never intended to commercialize their ideas or launch a startup, would benefit from learning to be entrepreneurial. And so the NSF’s experiment created another path by which innovation, a concept that prior to World War II barely registered as a cultural touchstone, became ingrained in our institutions, our educational system, and our beliefs about ourselves.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web